What are the levels of evidence?

In evidence-based practice, the term ‘evidence’ is used deliberately instead of ‘proof’. This emphasizes that evidence is not the same as proof, that evidence can be so weak that it is hardly convincing at all or so strong that no one doubts its correctness. It is therefore important to be able to determine which evidence is the most authoritative. So-called ‘levels of evidence’ are used for this purpose and specify a hierarchical order for various research designs based on their internal validity (see table below).

Internal Validity

The internal validity indicates to what extent the results of the research may be biased and is thus a comment on the degree to which alternative explanations for the outcome found are possible. Internal validity therefore is a measure of the strength of the cause-and-effect relationship between an intervention (or independent variable) and its outcome (dependent variable). The pure experiment in the form of a randomized controlled longitudinal study, also referred to as a randomized controlled trial (RCT), is in many disciplines regarded as the ‘gold standard’. Its study design is believed to yield the lowest chance of bias. Non-randomized studies, also referred to as quasi-experimental, observational or correlation studies, are regarded as research designs with lower internal validity. Examples of this type of research design include panel, cohort and case-control studies. Surveys and case studies are regarded as research designs with the greatest chance of bias in their outcome and therefore come low down in the hierarchy. Right at the bottom are claims based solely on experts’ personal opinions.

Internal vs External Validity

The levels of evidence are an indication for a study’s internal validity, but have no relation with a study’s external validity (generalizability). For instance, an RCT has a high internal validity, but may be less suited to generalization, which restricts its practical usability. Non-randomized longitudinal studies, on the other hand, have a lower internal validity, but can nevertheless be very useful for management practice.

Which Research Design for Which Question?

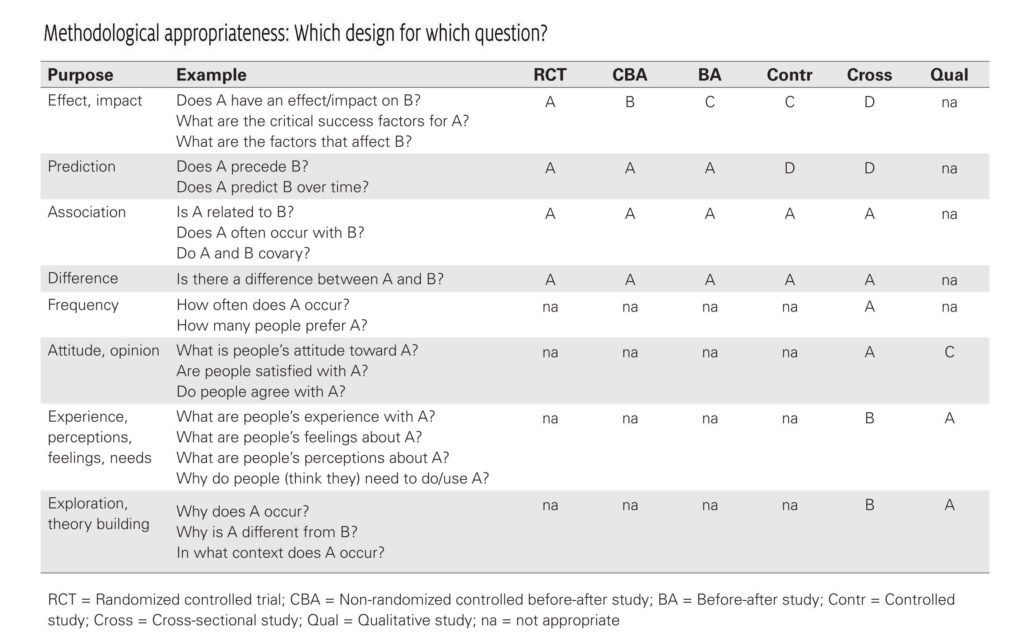

Different types of research questions require different types of research designs (see table below). Therefore you should always ask yourself: is this research design appropriate (or as optimal as possible) for the research question? A case study for instance is obviously not the most suitable design for assessing the strength of a possible cause-and-effect relationship, but it is clearly a strong design for assessing why or in which way an effect has occurred. Keep in mind that in management practice an answer to the question “what works?” sometimes is less relevant than the response to questions like “in what circumstances does it work” or “for whom does it work?” Therefore, from an EBMgt point of view, a study design is never strong or weak in itself: it all depends on the question and the availability.